The Fokker D.XIII

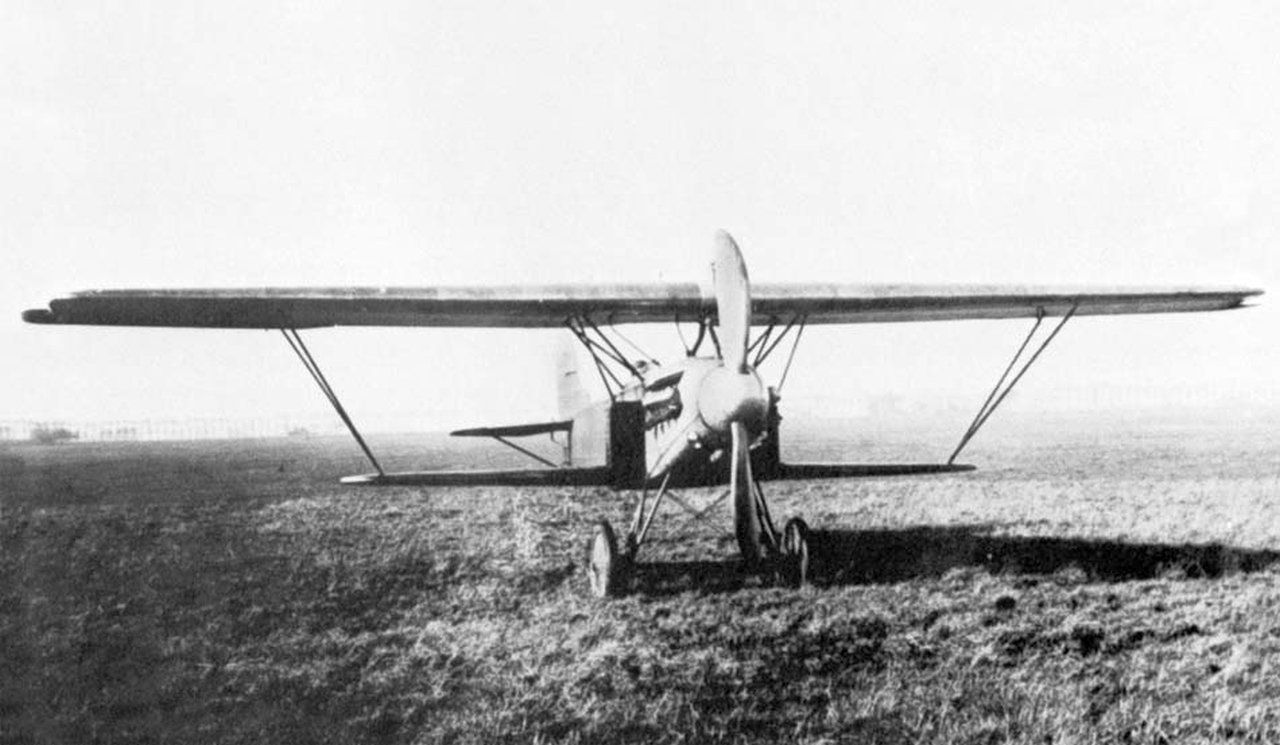

The D.XIII, designed by Reinhold Platz, was essentially an advanced version of the D.XI. It was faster, heavier and more expensive than its predecessor. This was due to its engine, a 450-hp Napier Lion that had considerably more power than the 300-hp Hispano-Suiza of the D.XI.

The D.XIII made its first flight on 12 September 1923. A month later, in October, the first customer was at the door: the Red Air Fleet. Two military test pilots, Aleksej Schirinkin* and Aleksandr Ljovin, came to Schiphol to make comparative test flights with the D.XI and the D.XIII. They found that the latter indeed had more potential, but could only be kept in check by experienced pilots. The training would therefore be expensive. Added to the high unit price, the Russians therefore decided to strengthen their air force with the D.XI, not with the D.XIII.

The Soviets subsequently purchased one D.XIII (c/n 4701) for evaluation. This aircraft was shipped to Russia in September 1924 and delivered in Moscow by Fokker factory pilot Emil Meinecke. The aircraft entered service with the NOA (the scientific test flight centre) and in January 1925 would become the aircraft of commander Ivan Pavlov, who had ЗА В.K.П.|Б| painted on the fuselage ─ an abbreviation of 'for the Communist Party of the All-Union (Bolsheviks)'.

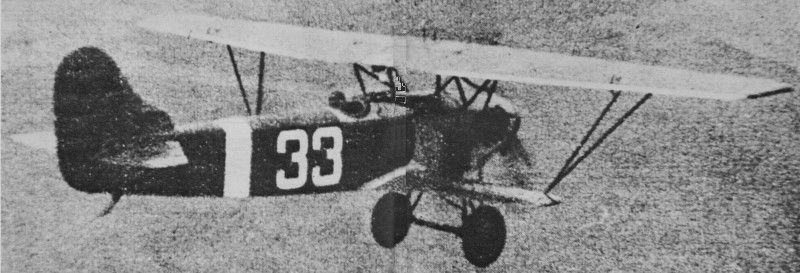

Another customer had already presented himself: the influential German industrialist Hugo Stinnes ordered fifty D.XIIIs on behalf of an unspecified client in South America. This turned out to be a facade, because once these D.XIIIs had been loaded onto a freighter, they did not set a course for South America, but for the then German seaport of Stettin. The real client turned out to be the German Reichswehr. From Stettin, the aircraft were shipped on to Leningrad in June 1925. The final destination was a secret German flying school near Lipetsk, Russia, where future Luftwaffe pilots were secretly trained**. The D.XIIIs were stationed there for many years. They did not bear German (or Russian) markings.

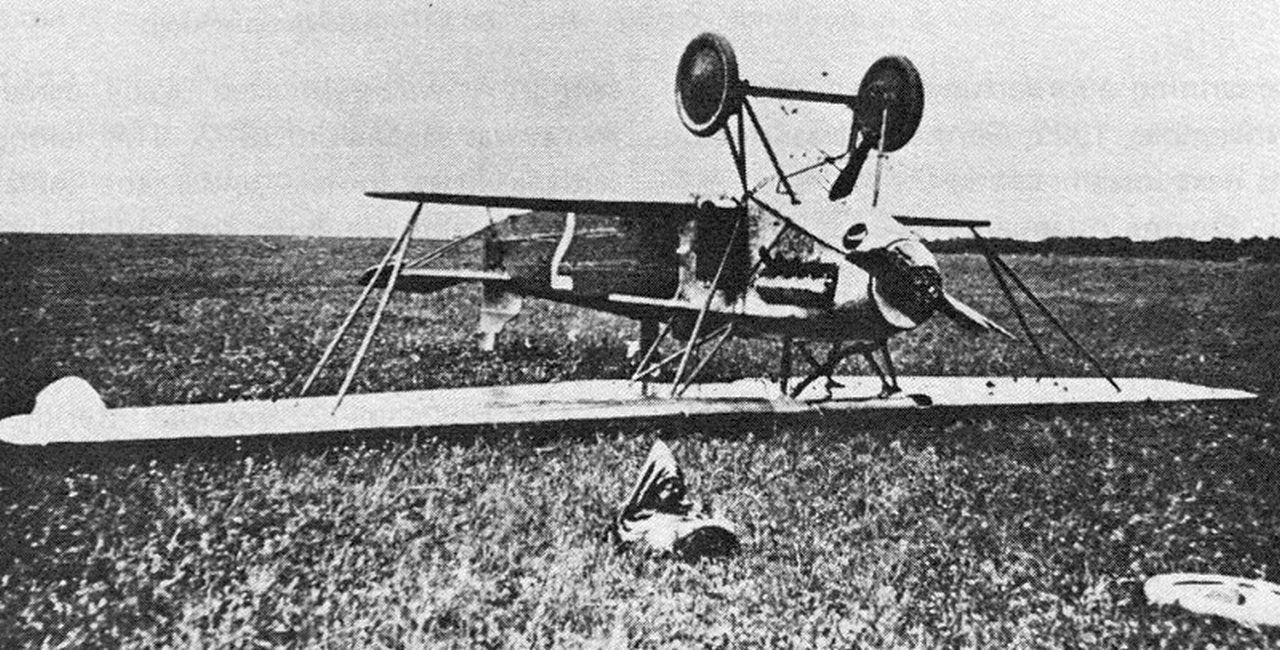

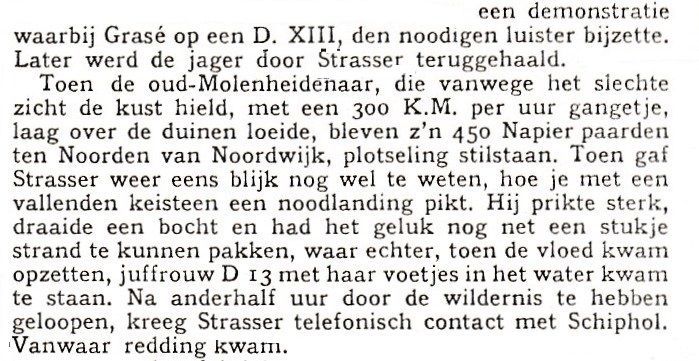

During 1924, a D.XIII was used by the Fokker factory for demonstration purposes. In August, this aircraft suffered engine trouble and had to make an emergency landing on a Dutch beach. It could not be brought to safety before the tide came in and was submerged. Whether this D.XIII was subsequently made airworthy again is not known.

In December 1924 a D.XIII was exhibited at the Paris Air Show. The aircraft attracted many spectators, but no buyers.

On 16 July 1925, Fokker's test pilot Bertus Grasé achieved four world speed records with a D.XIII. With a payload of 500 kg, he covered 100 km at a speed of 266 km/h. The Fokker D.XIII thus surpassed the best foreign fighter aircraft of that time, such as the British Gloster Grebe, the French Nieuport-Delage 42 and the American Curtiss PW-8 Hawk. Incidentally, the fastest in the world that year was the French Bernard (SIMB) V.2, a racing aircraft that managed to reach 448 km/h.

Many years later, in April 1932, a D.XIII with the civil registration D-2252 surfaced in Germany. The owner was the DVS (Deutsche Verkehrsflieger-Schule), a military training institute that posed as a school for airline pilots. Where this D.XIII came from is unknown.

In 1933, the flight school in Lipetsk closed its doors. The Germans left, leaving behind some thirty D.XIIIs that were transferred to the Red Air Fleet. But by 1933, the D.XIII was no longer the thing. They were hardly used by the Soviets - who were now building their own fighters - and were soon scrapped.

How many D.XIIIs were built in total? At least 52, and perhaps 56. 51 examples were sold and exported (see above) with construction numbers 4599-4628 (30), 4687-4706 (20) and 4865 (1). In addition, there were a few D.XIIIs whose context and construction numbers have not been clarified: the prototype, the drowned aircraft, the aircraft from the Paris Salon, the Grasé record machine and the DVS training aircraft. In theory, it could have been one and the same aircraft that always fulfilled a different role. That would bring us to 52. If it was not the same aircraft each time, the number could go up to 56.

* See, 'Schirinkin - Mokum Muscovite'

** See 'Lipetsk, the hidden flying school of the Germans',

Click on the photo to enlarge the photo

Key Resources:

- Archival material of the Aviodrome

- Verbotene Flugzeuge 1921-1935, HJ Nowarra (1980), pp. 100–101

- Soviet Aircraft and Aviation 1917-1941, L. Andersson (1994), p. 128–130

- Deutsche Spuren in der Sovjetischen Luftfahrtgeschicht, DA Sobolew (2000), blz. 74–89

Thanks to Klaas Kruijsdijk (Aviodrome), Andrej Averin and Gert Blüm.